Reading the Annunciation with The Bible of the Poor

Interpreting Luke 1:26–38

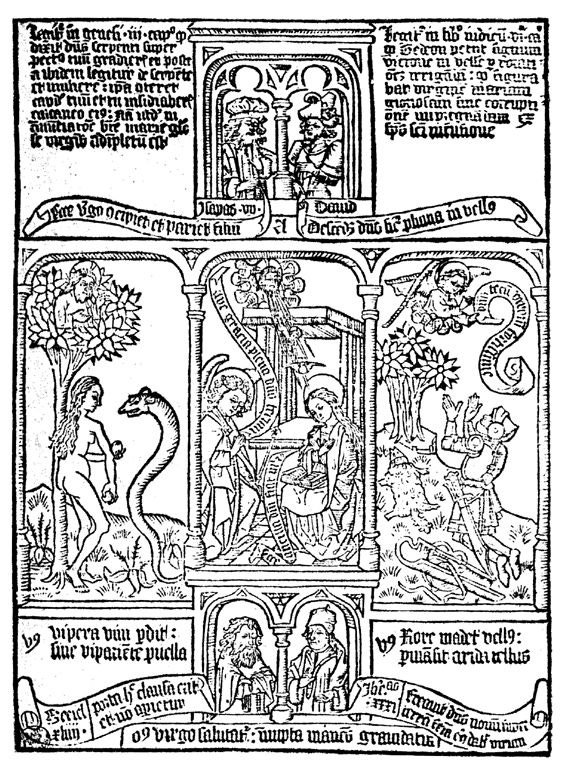

In the late-medieval period, the meaning of key New Testament events, like the Annunciation to Mary (above), could be represented and interpreted by incorporating what Christ-followers understood to be anticipatory Old Testament scenes and texts. This was a way to teach the spiritual truth of those events.1

The Biblia Pauperum, “Bible of the Poor,” casts biblical scenes, like stained-glass windows, in panels of three images produced from wooden blocks carved in relief (a.k.a. xylographs). Through this juxtaposition of images drawn from the Old and New Testaments, the basics of the faith could be taught to those who couldn’t read. Images of type and antitype appear side by side. Biblical passages in Latin helped those who could read guide those who couldn’t.

The Bible of the Poor depicts scenes in the life of Jesus, from his annunciation to the final judgment, thus identifying the christological center of the Old and New Testaments—the one pointing forward to the coming of Christ, the other celebrating his advent.

The Annunciation

In this example (above), we find a picturesque interpretation of the annunciation (Luke 1:26–38). The central panel depicts Gabriel’s announcement to Mary, the left panel portrays Eve’s temptation and sin at the hand of the serpent, and the right panel shows Gideon with his fleece, praying to God for a sign of victory. The artist interprets these scenes in three ways—first, through explicit references to and figural readings of Old Testament texts; second, by the details of the portraits themselves; and third, by positioning these scenes in relation to each other.

The essay continues after this recommendation.

Albert C. Labriola and John W. Smeltz, trans., The Bible of the Poor (Biblia Pauperum): A Facsimile and Edition of the British Library Blockbook C.9 d.2 (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1990). ISBN 9780820702307. 190 pp.

This fascinating book is available from Duquesne University Press at a much more reasonable price than the asking price among other booksellers.

Images like the one above appear first, followed by translation and commentary.

Eve and the Serpent

The portrait of Eve and the serpent is accompanied by the following declarations and passages:2

“We read in Genesis 3 that the Lord said to the serpent, ‘On your belly you will crawl,’ and in the next verse we read of the serpent and the woman: ‘She will crush your head and you will lie in wait for her feet.’ For indeed this event is fulfilled in the annunciation of the glorious blessed Virgin Mary.”

“Isaiah 7: Behold a virgin will conceive and bear a son.”

“The serpent is ruined, the maiden giving birth without pain.”

“Ezekiel 44: This gate will be shut, and it will not be opened.”

Gideon

The portrait of Gideon is accompanied by the following:

“We read in Judges 6 that Gideon sought a sign of victory in a fleece filled with dew. This event prefigured the glorious Virgin Mary made pregnant without violation by the infusion of the Holy Spirit.”

“David: The Lord will come down like rain on the fleece.”

“Hail, full of grace, the Lord is with you. Behold the servant of the Lord; may it be done to me.”

“The Lord is with you, most mighty one.”

“Jeremiah 31: The Lord created a new thing on the earth; a woman will protect a man.”

The Annunciation

Across the bottom of the whole is this banner: “The Virgin is saluted; she is impregnated, yet remains a virgin.”

The focal point of this xylograph is the annunciation itself, Gabriel’s announcement to Mary predicting the birth of a son.3 In addition to portraying the interaction of the angel and the virgin, the artist depicts the Spirit’s coming upon Mary, signifying that the annunciation marks the moment of virginal conception.

In fact, the wood cutting shows rays traveling from the Father toward Mary, carrying with them the Son and the Holy Spirit, so that her pregnancy is shown to be the result of the gracious intervention of the Triune God.

Mary, Eve, Gideon

Mary remains sexually innocent, depicted as pure, modest, and humble. She has an open Bible on her lap, exhibiting her spiritual devotion. Is she reading the scriptural texts noted in the accompanying panels? Is she reading the scriptural songs of Moses and Miriam, Hannah and Deborah?

Eve, by way of contrast, is depicted as prideful, immodest, and sinful, demonstrating the deliberate pairing of Eve and Mary, with Mary overturning the curse set in motion by Eve’s action in Eden. Mary is modestly dressed, seated, face down, arms folded, while Eve is nude, standing, head held high with eyes directed at the serpent-tempter, her arm extended toward the source of temptation, her hand holding what appears to be an apple.

Gideon is portrayed petitioning God for a sign of victory, with the fleece he places before God symbolizing in its wetness both Mary’s pregnancy and the child to be born to her. This fleece, a divinely provided emblem of victory, identifies the Messiah with the lamb, whose triumph over evil is realized in self-sacrifice. Gideon’s promised victory thus prefigures the conquering Christ.

Texts and images, taken together, thus portray Gabriel’s announcement of Jesus’s birth to Mary as having been anticipated by both prophetic word and scriptural prefiguration.

This material is adapted from my book, Discovering Luke: Content, Interpretation, Reception, Discovering Biblical Texts (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans; London: S.P.C.K., 2021).

Citations are from Albert C. Labriola and John W. Smeltz, trans., The Bible of the Poor (Biblia Pauperum): A Facsimile and Edition of the British Library Blockbook C.9 d.2 (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1990), 99, with amendments.

For a more thorough interpretation (from which I have selectively drawn), see Labriola and Smeltz, Bible of the Poor, 143–45.