Mary, Powerful in the Scriptures

Luke Presents Mary as an Exemplary Believer

Luke’s birth narrative opens its windows wide to God’s coming to bring peace, restoration, salvation. It also begins to lay the groundwork for describing those patterns of life that will characterize those who welcome and embrace God’s good news.

Luke presents Mary, Jesus’s mother, as an exemplary disciple—one who departs from the typical script written for young women in ways that mark her as both a model believer and an exemplary agent of the new age coming to fruition in Jesus’s coming. Here, I focus on just one often-overlooked way in which this is true.

Powerful in the Scriptures

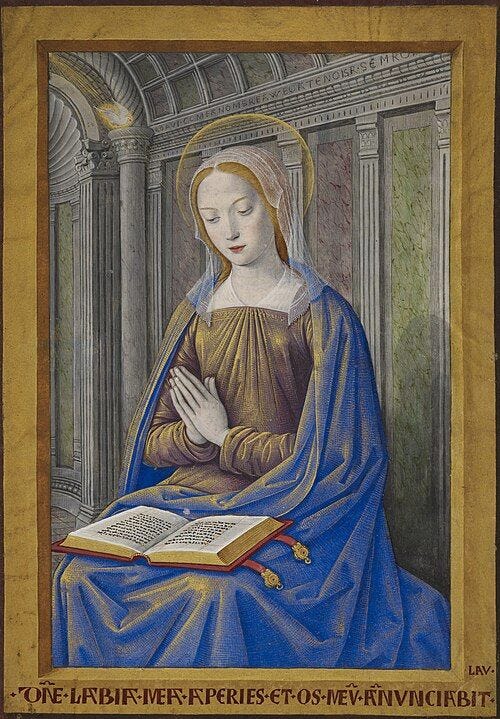

Already in the early church, Mary was known as a young woman “powerful in the Scriptures,” to borrow an apt phrase from Luke’s introduction of Apollos, the Alexandrian Jewish follower of Jesus (Acts 18:24 AT).1 “Mary knew the law,” Origen writes. “She was holy, and had learned the writings of the prophets by meditating on them daily” (Hom. Luc. 6.7). Indeed, artistic renditions of Mary often depict her with the Bible in her hands, sometimes sitting in what looks like her personal library. Ambrose lists “studious in reading” among her virtues (Virg. 2:2.7, 10).

Of course, the adulation of Mary among these and other early writers sometimes exceeds the boundaries of the New Testament evidence, reflecting instead the role of the virtuous woman as understood in the days of Origen or Ambrose. Such writers were often at pains to defend Mary’s virtue in the face of the challenges she presented, not the least of which was her pregnancy outside of marriage. Regarding her grasp of the Scriptures, however, Luke himself provides evidence in the form of the Magnificat, which is replete with scriptural phrases and resonances.

The Magnificat

First, then, the text of the Magnificat, Mary’s Song:

Mary said,

“With all my heart I glorify the Lord!

In the depths of who I am I rejoice in God my savior.

He has looked with favor on the low status of his servant.

Look! From now on, everyone will consider me highly favored because the mighty one has done great things for me.

Holy is his name.

He shows mercy to everyone, from one generation to the next, who honors him as God.

He has shown strength with his arm.

He has scattered those with arrogant thoughts and proud inclinations.

He has pulled the powerful down from their thrones

and lifted up the lowly.

He has filled the hungry with good things

and sent the rich away empty-handed.

He has come to the aid of his servant Israel, remembering his mercy,

just as he promised to our ancestors, to Abraham and to Abraham’s descendants forever. (Luke 1:46–55)

Mary’s Song and Israel’s Scriptures

Mary’s Song is like a collage of praise hymns found in Israel’s Scriptures, including the Songs of Moses and Miriam (Exod 15), Deborah (Judg 5:1–31), and especially Hannah (1 Sam 2:1–10). To give one illustration, the profound sociopolitical reversal to which Mary’s Song testifies finds a ready precursor in Hannah’s Song:

The Lord!

He makes poor, gives wealth,

brings low, but also lifts up high!

God raises the poor from the dust,

lifts up the needy from the garbage pile.

God sits them with officials,

gives them the seat of honor! (1 Sam 2:7–8)

Moreover, like Mary’s Song, so too Hannah’s Song centers on God’s goodness to Hannah while extending her celebratory words to include God’s vindication of God’s people, whom Hannah and Mary represent. Indeed, in a psalm sung before Passover, Hannah’s words make a cameo performance, celebrating God’s work in exodus:

God lifts up the poor from the dirt

and raises up the needy from the garbage pile

to seat them with leaders—

with the leaders of his own people! (Ps 113:7–8)

Mary’s Song belongs to the same hymnic impulse to celebrate God’s deliverance of God’s people, now through Mary’s son.

We can discern parallels, too, between Mary’s Song and Ps 136, that profound and detailed tribute to God’s faithful love: “God remembered us when we were humiliated” (v. 23), God acted “with a strong hand and outstretched arm” (v. 12), and God “struck down great kings” (v. 18). Moreover, the fabric woven into the garment of Mary’s Song, imprinted with images of God’s liberation of Israel from Egypt, is on full display in Ps 136: God’s mercy toward Israel is shown when he “split the Reed Sea,” “brought Israel through,” and “tossed Pharaoh and his army into the Reed Sea” (vv. 13–15).

Scholars since the late eighteenth century might deny the possibility of a teenage girl formulating such a hymn, but this is precisely what Luke portrays. What is more, among characters within the Third Gospel, Mary, interpreter of Scripture (Mary, who knows, understands, and proclaims the Scriptures), is in rarefied company.

Those among Jesus’s innermost circle of followers lack her insight; Jesus himself must first open their minds to understand the Scriptures (Luke 24:45), which they then interpret, empowered by the Holy Spirit, in the book of Acts.

The devil proves to be an unreliable interpreter of Israel’s Scriptures (4:1–13).

Neither can we rely on the exegesis of those legal experts who wrestle with Jesus concerning God’s agenda as revealed in the Scriptures.

Once Zechariah is filled with the Spirit, he can interpret the Scriptures well (1:67–79).

Simeon and Anna demonstrate scriptural insight (2:25–38).

We might say, then, that Mary and, apart from Jesus, very few others model in Luke’s Gospel the dexterity with the Scriptures that will characterize Jesus’s witnesses in the Acts of the Apostles.

Powerful in the Scriptures, Mary exemplifies faithfulness to God and God’s agenda.

What Does It All Mean?

On a related note, Luke twice reports that Mary contemplated in her heart everything she was learning (2:19, 51). Luke’s phrasing may remind us of occasions in Israel’s Scriptures when people pondered the significance of such revelatory moments as a dream (Gen 37:11) or vision (Dan 7:28). Apparently, even extraordinary events like these require reflection to hit on the right meaning. For Luke, such contemplation presses one further into the Scriptures in search of the patterns of God’s faithful work; it calls us to a quest for meaningful categories for making sense of God’s saving activity.

Meditation takes place in “the heart”—in ancient psychology, the center of affect, comprehension, and volition. Mary doesn’t jump to conclusions but engages in the sort of careful reflection that goes all the way down to the roots of discernment and faithful response. Contrast Mary’s slow, deliberate, interpretive work with Peter’s hasty response to Jesus’s transfiguration and to seeing Jesus with Moses and Elijah: “Master, it’s good that we’re here. We should construct three shrines: one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” Peter’s impetuous, muddleheaded perception attracts Luke’s censure, “But he didn’t know what he was saying,” as well as God’s corrective voice: “This is my Son, my chosen one. Listen to him!” (Luke 9:33–35). Mary, not Peter, shows the way.

Luke’s birth account closes with Mary’s contemplation, not with final answers, social-media catchphrases, or even well-crafted propositions, and this encourages Luke’s audience, then and now, to respond similarly. Rather than formulating hasty conclusions about what is or must be, Luke’s auditors and readers would do well to follow the path Mary has opened: delving into the Scriptures and remaining open to the course Luke’s own narrative follows. “The events that have been fulfilled among us” (1:1)—their true significance requires dedicated engagement with Israel’s Scriptures, ongoing contemplation, and, of course, the rest of the story Luke is telling.

Unless otherwise indicated, all scriptural citations follow the Common English Bible. This material is adapted from my book, Discovering Luke: Content, Interpretation, Reception, Discovering Biblical Texts (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans; London: S.P.C.K., 2021).

But was Mary pondering? See https://doi.org/10.1163/15685365-bja10040