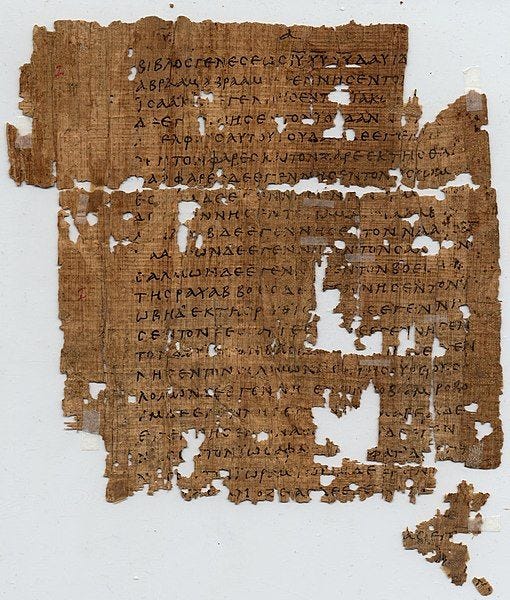

Papyrus 1 (ca. 250 CE), recto, the beginning of Matthew’s Gospel (source: Wikimedia Commons).

Critics of the theological interpretation of Scripture often complain about how much time theological interpreters spend clearing their throats, so to speak (talk, talk, talk about “method”), rather than just doing the work of theological interpretation. Get on with it, they say. Show us what it looks like!

This is an important criticism, though perhaps you will agree with me that it is significantly mitigated by three considerations:

Theological interpreters have produced a wide range of materials, including commentaries, such as the Two Horizons Commentary on the New Testament, the Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible, the Belief series, and the Two Horizons Commentary on the Old Testament. The recently initiated series Commentaries for Christian Formation clearly falls under the umbrella of theological interpretation, too. Are these efforts consistently successful in representing what we mean by “theological interpretation”? This is debatable (see the open-access essay by W. Ryan Gutierrez, “New Testament Theology and the Production of Theological Commentaries: Trends and Trajectories,” Religions 12, no. 11 [2021]: 949; https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12110949 ; as well as Seth Heringer“The Problem of ‘History’ in Recent Theological Commentary,” in Ears That Hear: Explorations in Theological Interpretation of the Bible, edited by Joel B. Green and Tim Meadowcraft [Sheffield, UK: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2013], 26–42), but they do represent something of the range of ways this interpretive approach is understood and practiced. And, of course, the Journal of Theological Interpretation and the Journal of Theological Studies Supplement Series (Eisenbrauns; now Explorations in Theological Interpretation [Baylor University Press]) include a regular diet of such efforts.

Concerns with history (vs. theology) have served as the center of gravity of biblical studies for so long that “critical biblical scholarship” is practically equated with historical criticism. Breaking away from the pull of its gravity requires significant work, some of which needs to be done at a more theoretical level.

Interestingly, the same complaint (Too much throat-clearing!) does not seem to bother those concerned with the range of historical-critical approaches on offer today at the biblical studies smorgasbord. Just turn the pages in publishers’ catalogs and take note of how often you find another volume on interpretive methods….

Even so, it’s worth stepping back in order both to represent what theological interpretation looks like in practice and to recommend three or four specimens of work (other than commentaries).

Theological Interpretation in Practice

It isn’t possible in a short post to provide a fully developed reading of a text, but we can take a compass reading or two.

1 Peter 1:1–2

Peter, apostle of Jesus Christ, to the chosen, strangers in the world of the diaspora in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, in the sanctification of the Spirit, because of the obedience and sprinkling of the blood of Jesus Christ: May grace and peace be multiplied to you. (AT)

The beginning of 1 Peter invites a range of questions, though the typical ones revolve around (1) the location of the audience in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, and (2) the ethnic identity of Peter’s recipients. Fair enough.

Without neglecting those two questions, what theological interpreters want to prioritize is a different take on context.

Contra the tendency to imagine that “the strange world of the Bible” requires more and more sociohistorical digging, Karl Barth recognized in his 1916 lecture on “The Strange New World within the Bible” that the “stuff” (Sache) of the Bible is not fundamentally about human history, human practices, and the like.

The Bible tells us not how we should talk with God but what he says to us; not how we find the way to him, but how he has sought and found the way to us; not the right relation in which we must place ourselves to him, but the covenant which he has made with all who are Abraham’s spiritual children and which he has sealed once and for all in Jesus Christ. It is this which is within the Bible.

He concludes, “We have found in the Bible a new world, God, God’s sovereignty, God’s glory, God’s incomprehensible love.”1 The pressing question, then, is not simply how we might span the cultural chasm(s) identified by academic biblical scholarship, between our world and those of the biblical texts, but, perhaps even more pressing: How might we span the theological chasm from the theological imaginaries of these scriptural texts and our own taken-for-granteds? Are we ready to have our hearts and minds changed by what the text tells us of God, of ourselves, of our world?

In this case, we become model readers of this text largely by coming to terms with our own identities as “chosen” and “strangers in the world,” understood according to the trinitarian framework by which the letter’s readers are identified: “according to the foreknowledge of God the Father, in the sanctification of the Spirit, because of the obedience and sprinkling of the blood of Jesus Christ.” (This does not mean we imagine the author’s grasp or acceptance of the developing credal tradition formulated in terms of the Three-One God. Neither are we allergic to seeing how the credal traditions we find in letters like this one provide hints and patterns that press in a trinitarian direction.)

In this way, working with 1 Pet 1:1–2 is not merely an objectivizing enterprise by which we examine and work to understand the history and culture it takes for granted. It is a self-involving enterprise that invites us to come to terms with who God is and what God is up to, along with who we are and how we work out conversionary lives in relation to this opening address.

Mark 1:9–11

In those days Jesus came from Nazareth of Galilee and was baptized by John in the Jordan. And just as he was coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens torn apart and the Spirit descending like a dove upon him. And a voice came from the heavens, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.” (NRSVue)

In the premodern era, it was common to find in this scene a reference to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—a view represented well in Origen’s observation: “In the baptism of Jesus, the Father bore witness, the Son received witness and the Holy Spirit gave confirmation—thus in the Jordan the triune mystery began to be disclosed.”2

Recent commentary has been less forthcoming theologically. For example, in the Hermeneia volume on Mark’s Gospel, Adela Yarbro Collins refers to our scene as a biographical or cult legend that uses intertextuality to show that, from a perspective shaped by Homeric epic, after his baptism Jesus was regarded as “a divine being walking the earth”; or, from a perspective shaped by Israel’s Scriptures, at his baptism God appointed Jesus as the messiah and servant of the Lord.3 (Note how, in both readings, Collins prioritizes background for making sense of the scene Mark paints.)

Without requiring an identification of the Second Evangelist as a Nicene signatory, we can nonetheless observe that his prologue (Mark 1:1–15) is saturated with references to:

God—God’s coming, God’s having a son, God’s royal rule, and the tearing of the heavens in order to facilitate God’s presence at Jesus’s baptism;

Jesus—the Christ, Son of God, the Lord before whom the messenger is sent, the Stronger One who will baptize with the Holy Spirit, God’s Anointed King, the one in whom God finds happiness, the Servant of Yahweh whose wilderness temptation portends paradise, and the one whose mission is synchronized and identified with the good news that God reigns;

The Holy Spirit—with whom the Stronger One will baptize, whom God sends to anoint Jesus for his messianic vocation, and who, as an actant in his own right, propels Jesus into the wilderness.

Accordingly, we recognize that, in Mark’s narrative, the Father is the father of the Son, the Father sends the Son, the Father speaks of the Son, the Father sends the Spirit, the Spirit propels the Son, the Son baptizes with the Spirit, and the Son decisively discloses God’s royal rule and calls on people to orient their lives to God’s royal rule. In Mark’s narrative trinitarianism,4 the Father is known in relation to the Son, the Son is known in relation to the Father, and both are known in relation to the Holy Spirit. Origen thus speaks well when he writes: “Thus in the Jordan the triune mystery began to be disclosed.” This is not because Mark, writing in the latter half of the first century, was a theologian of the Three-One God, but because we, whose faith is shaped by the church’s Rule of Faith, find language and patterns and scaffolding for reading Mark’s Gospel through a trinitarian lens.5

Recommended Reading

[Note: As an Amazon Associate, I may earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase. This doesn't affect the price you pay and helps support this website.]

Robert W. Jenson, Canon and Creed, Interpretation: Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2010). ISBN 9780664230548. 152 pp.

After discussing the relationship of canon and creed historically, Jenson devotes “part three” of the book to “creed/dogma and scriptural exegesis.” He identifies the creed as “critical theory for Scripture” (a promising proposal) and provides three sermons to exemplify what this might look like.

Joel B. Green, Practicing Theological Interpretation: Engaging Biblical Texts for Faith and Formation, Theological Explorations for the Church Catholic (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012). ISBN: 9780801039638. 160 pp.

This volume comprises four case studies in theological interpretation of the Bible: on James, on theological anthropology, on theology and history, and on a Wesleyan reading of foreknowledge.

Murray A. Rae, Resurrection and Renewal: Jesus and the Transformation of Creation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2024). ISBN 9781540966209. 208 pp.

Rae presents the resurrection as history’s turning point and the decisive window into what is going on in the world. He doesn’t try “to prove” the resurrection, but takes it as a given reality. He examines the gospel accounts, reads the resurrection in relation to God’s promises to Israel in Israel’s Scriptures, and analyzes its formative role in Paul's life and theology. Rae explores resurrection’s implications for understanding Christ, salvation, the future, mission, church, and history’s purpose, as well as its impact on Christian living and ethics. An important representation of the marriage of systematic theology and engagement with Scripture.

Matthew Croasmum and Miroslav Volf, The Hunger for Home: Food and Meals in the Gospel of Luke (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2022). ISBN 9781481317665. 114 pp.

Examining Luke’s many meal scenes, this short book exudes exegetical wisdom while never losing itself in the dense undergrowth of the theological forest. Jesus reveals his nature and mission in the breaking of the bread while at the same time disclosing the true home to which the human family is invited. We are drawn to it by its delectable smells and tastes, but also by the nature of these guest lists, these table companions, this table talk. For Luke, “a meal is a site of nourishing mutual encounter among (a) people—rich and poor, sinners all; (b) places—both the dwellings where meals happen and the fields and wilds whence food comes; and (c) God—as the Creator of the people, the dwellings, the fields, and the wilds and as reconciler of all to one another in drawing all together toward consummation as the home of God” (75). Among those who read Luke’s Gospel as Scripture, Luke’s meal scenes prompt table practices that draw their inspiration, example, and significance from Jesus’s. A profound theological interpretation of Luke’s Gospel in the service of Christian practice and Christian flourishing.

Karl Barth, “The Strange New World within the Bible,” in The Word of God and the Word of Man (Gloucester: Peter Smith, 1978), 28–50 (43, 45).

Cited in Mark, ed. Thomas C. Oden and Christopher A. Hall, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: New Testament 2 (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1998), 11.

Adela Yarbro Collins, Mark: A Commentary, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2007), 146–51 (149).

See further, Hallur Mortensen, “The Baptismal Episode as Trinitarian Narrative: Proto-Trinitarian Structures in Mark’s Conception of God” (PhD diss., Durham University, 2018).

For this example, I am adapting earlier material from my essay, “What Is ‘Theological’ about Theological Interpretation,” Wesleyan Theological Journal 58, no. 1 (2023): 30–41.