Who Is a Christian?

A Contemporary Enigma

Several years ago, a friend surprised me with his refusal to call himself a Christian.

We had been lamenting the loss of the word evangelical from our vocabularies. What could be problematic in a reference to the evangel, τό εὐαγγέλιον, the good news, the gospel? A half century ago, not least among supporters of the Moral Majority, the term evangelical became yoked to a conservative political movement. Today, not least in major media outlets, on social networks, and among pollsters, the term seems to refer mostly to a reliably conservative voting bloc. Reality may require more nuance (e.g., Richard Flory, “Five Kinds of American Evangelicals and Their Voting Patterns”), but such careful distinctions are hard to maintain in a social-media-defined, bumper-sticker-labeled world. Accordingly, my friend and I observed, we rarely refer to people and institutions any longer as evangelical.

That’s when he dropped his surprise.

“I don’t even call myself a Christian anymore,” he went on to say. Silence. Finally, I asked, “Well, what are you, then?” “I’m a Jesus-follower,” he replied.

Christian … in the Public Eye?

I was surprised then, but no longer. Whatever the term Christian signified in the past, I sometimes struggle today to put my finger on common usages, especially in public statements. I asked a few people to help me, and here is some of what I heard:

I’m a Christian = I’m among the privileged.

I’m a Christian = Of course we have an American flag in our church sanctuary!

I’m a Christian = I’m going to heaven.

I’m a Christian = I’m a good person.

I’m a Christian = I’m “in” (and you’re / they’re “out”).

I’m a Christian = I think Congress should mandate Christian morality.

I’m a Christian = You owe me your trust.

I’m a Christian = The Ten Commandments need to be posted in our schools.

I’m a Christian = There’s no room here for Muslims.

Too cynical? Maybe. Remember, though, we were thinking of public (sometimes even slang) usage. And I haven’t even mentioned those times when the use of Christian seems designed to draw divisions around race or ethnicity, citizenship, and the like.

My friend spends a lot of time with unchurched folk, a lot of time, so his decision to steer clear of the use of the Christian label may well be a prudent one.

Christian … Early Uses

I know, I know, word-meanings shift with usage, so old words drop out and new words enter our working dictionaries. (Five years ago, who would have imagined hearing me use the word bougie?) Still, it might be helpful to look briefly into the origins and earliest uses of the term Christian, if only to get our bearings.

In the New Testament, Christian translates (or is a transliteration of) the Greek term Χριστιανός (Christianos), itself a derivation of the Latin Christianus. The Latin suffix -anus and the Greek -ιανός (-ianos) have been appended to the proper name Christ. Morphologically, these suffixes denote someone’s follower, supporter, partisan, or adherent—in this case, a Christ-follower. A close analogy in the Gospels is the word Herodian (Ἡρῴδης + -ιανός, Hērōdēs + -ianos): a Herod-supporter (Matt 22:16; Mark 3:6; 12:13).

According to Acts 11:26, “It was in Antioch where the disciples were first labeled ‘Christians’” (Common English Bible). From this claim, we gather that

This label was given to the disciples by people who were not themselves Jesus-followers,

This label was likely given to Jesus’s disciples by gentiles (who would have trafficked in Latin), and

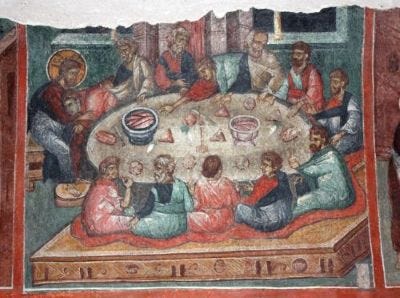

Calling Jesus’s followers Christians meant that they had some qualities that distinguished them from other Jews (just as Pharisaism represented an option for living out one’s faith as a Jew). (Accordingly, in these days of the Jesus-movement, Christian was one among other options for living as a Jew.) An examination of the earlier material in Acts supports the view that those distinguishing qualities center on their strange reading of Israel’s Scriptures, their strange claim that Jesus is God’s Messiah, and their strange habits of economic sharing, table fellowship, and the like.

Outside of Acts, Peter’s instruction is especially telling: “Yet if any of you suffers as a Christian, do not consider it a disgrace, but glorify God because you bear this name” (1 Pet 4:16 NRSVue). Here, Christian appears alongside other charges that might be brought against Christ-followers: “murderer, a thief, a criminal, or even … a mischief maker” (4:15). This encourages the view, again, that Christian is a label given by outsiders—in this case, clearly, by opponents. Indeed, 1 Peter overflows with references to its hearers and readers as people who suffer vitriol, slander, and other forms of social abuse on account of their identification with Christ.

This means that the central quality that gives a person or group their identity is this: allegiance to Christ. All other characteristics fade in comparison. And this badge, this allegiance to Christ, presumes identification with Jesus of Nazareth—in 1 Peter, suffering as he suffered, walking as he walked, and so on.

Early on, calling someone a Christian was a shaming act, an attempt to associate someone ignominiously with the Jesus who suffered the ultimate humiliation of a Roman cross. Recognizing this, Peter transforms humiliation into honor—not by celebrating one’s accomplishments as these might be measured in the wider world (one’s position, one’s net worth, one’s beauty, and so on), but by recognizing that the honor sought by Jesus’s followers is (or should be) God-given and not society’s reward for conforming to its standards.

The stigma of social rejection “for the name of Christ,” living out-of-step lives through following in Jesus’s steps—this signifies honor before God. (Cf. 1 Pet 2:21; 4:14.)

Who Is a Christian?

In time, followers of Jesus, Jews and gentiles, would come to use the term Christian as a self-designation. It’s important to remember, though, that the term was first used by outsiders—outsiders who recognized this single, most important quality of the people they were labeling: the witness of their lives recalled the witness of Jesus to God’s royal rule. They wore “Christ” on the garments of their lives. Christ was for them the primary identity marker. By this definition, Christians are known by others for their peculiar, out-of-step patterns of life, patterns of life that New Testament writers might classify as diaconal (service-to-others-oriented) and cruciform (shaped by the cross of Christ).

Want to Go Deeper? Suggested Reading

David G. Horrell, “The Label Χριστιανός: 1 Pet 4:17 and the Formation of Christian Identity,” Journal of Biblical Literature 126 (2007): 361–81; https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10036/36813/JBL%20Christianos%20article.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

Paul Trebilco, Self-Designations and Group Identity in the New Testament (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 272–97.

As Jesus was a disruptor of his cultural, religious, economic, political environment, to adopt the name Christian implies a deliberate reflection of him.

I’ve wondered if the significance of that first use of the term had to do with outsiders making sense of that newfangled multilingual/-cultural group of Hellenists and Hebrews come together in Antioch in an unprecedented unity (cf., 11:20), especially given the cotext (w/ the Holy Spirit recognized as being “poured out even in the Gentiles,” 10:45) and its placement in the literary development of the book. In other words, could the sense of it be that at this point in Acts we’ve arrived at the formation of a new kind of community with no other obvious organizing principle than the name in which they gathered?