Theological Interpretation of Scripture Matters—7

What about "Historical Criticism"?

The contemporary renaissance of theological interpretation of the Bible has raised perplexing questions about the relationship between this renewed, theological enterprise and historical criticism and historiography in biblical studies. This is not surprising.

Theology vs. History

The problematic nature of history for theological interpretation is the inevitable consequence of the segregation of “theology” from “history” in biblical studies in the modern era. This is not to say that “theology” has been completely exorcized from critical biblical studies. After all, many interpreters continue to write about “the theology of the Yahwist,” say, or “the theology of Thomas,” or “the theology of Matthew’s Gospel.” The sort of “theology” sponsored by modernist, critical biblical studies, however, is entirely devoted to the descriptive enterprise. Consequently, at the hands of modern biblical studies, theology is itself a historical enterprise and, as such, it is historically determined.

If one wants to move beyond the question of what ancient people thought about God or how they understood God to have addressed them, additional work is necessary. And this work is normally done not so much by biblical scholars as by homileticians or theologians or ethicists, or by biblical scholars who, for the sake of applying the results of historical scholarship, have temporarily donned the hat of the preacher, pastor, or theologian.

God can speak today only after history has spoken.

Theological Interpretation Has Its Questions

Theological interpretation has taken a critical stance with respect to this vision of biblical studies.

Rather than reduce the serious study of the Bible to the descriptive task, how might the Bible itself be engaged theologically? Rather than inquiring how theology might be done on the basis of Scripture, can we (re)imagine how to do theology with Scripture?

What is meant by historical criticism? It is one thing to critique the enterprise of historical study as it has been formulated since the nineteenth century, but quite another to inquire into how historical study might shape our thinking about earlier times and places—their practices, their patterns of life—so that we understand better the witness of Scripture.

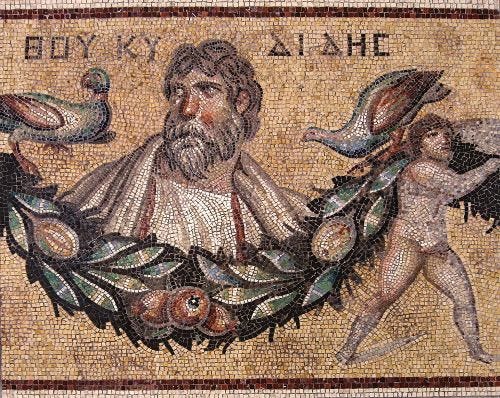

Recent work in both the theology of history and the philosophy of history raises serious questions against over two centuries of attempts by biblical scholars, self-identified as historians, at reconstructing the history to which the biblical materials bear witness—including, say, the historical Moses or the historical exodus or the historical Jesus.

As a side note, I should observe that some theologians involved in theological interpretation articulate a more sanguine attitude toward “historical criticism” than do many biblical scholars who see themselves as contributing to theological interpretation of Scripture. I think this is because practitioners trained in these two enterprises understand “historical criticism” quite differently.

Suggested Reading

Let me call your attention to some recent publications that reflect on questions such as these. [Note: As an Amazon Associate, I may earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase. This doesn't affect the price you pay and helps support this website.]

Joel B. Green, “Rethinking ‘History’ for Theological Interpretation,” Journal of Theological Interpretation 5, no. 2 (2011): 159–74; repr. in Joel B. Green, Luke as Narrative Theologian: Texts and Topics, WUNT 446 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2020), 24–37. https://doi.org/10.2307/26421422

PDF available here.

In recent years, theological interpretation of Christian Scripture has often been distinguished by its wholesale antipathy toward history and/or historical criticism. Working with a typology of different forms of “historical criticism,” this essay urges:

that historical criticism understood as reconstruction of “what actually happened” and/or historical criticism that assumes the necessary segregation of “facts” from “faith” is inimical to theological interpretation;

that this form of historical criticism is increasingly difficult to support in light of contemporary work in the philosophy of history; and

that contemporary theological interpretation is dependent on expressions of historical criticism concerned with the historical situation within which the biblical materials were generated, including the sociocultural conventions they take for granted.

Murray A. Rae, History and Hermeneutics (London: T&T Clark, 2006). ISBN: 9780567080929. 176 pp.

Rae, a theologian from New Zealand’s University of Otago, has written a critical examination of contemporary biblical interpretation, arguing that modern hermeneutical approaches have been fundamentally compromised by problematic assumptions about the nature of history itself. The book serves as both a critique of current methodologies and a constructive proposal for a more theologically grounded approach to Scripture. His argument centers on the claim that contemporary biblical hermeneutics has been radically impaired by widespread acceptance of secular historical assumptions that are incompatible with faithful biblical interpretation. These assumptions, rooted in Enlightenment thinking, treat history as a purely naturalistic phenomenon, thereby undermining the Bible’s understanding of divine action.

As an alternative, Rae proposes a theological account of history built around two fundamental categories: creation and divine promise. Within this framework, history is not merely a sequence of human events but rather the unfolding of God’s purposes in creation. The resurrection is a history-making event by which the aim of history is disclosed, one that reveals who Jesus truly is—a reminder that history-writing is never a simple description but always an interpretive enterprise. To discard out of hand Scripture’s witness to Jesus on account of its testimonial character, he insists, is philosophically untenable. Moreover, since the church confesses and participates in the reality of Jesus Christ revealed in the Scriptures, reading and comprehending Scripture is an essentially ecclesial practice.

Rae’s theological conception of history provides the proper context for understanding Scripture on its own terms, rather than forcing it to conform to modern historical-critical methodologies. He provides, then, a far-reaching philosophical critique, as well as guidance for reading the Bible as the church’s book, grounded in a robust theological understanding of history as the sphere of divine action.

Seth Heringer, Uniting History and Theology: A Theological Critique of the Historical Method (Minneapolis: Fortress Academic, 2018). ISBN: 9781978700369. 262 pages.

Heringer, a theologian at Toccoa Falls College, presents a fundamental challenge to the way theologians and biblical scholars have approached historical investigation. He argues that scholars have made a critical error by adopting the historical-critical method as their primary tool for making historical claims about the past. This approach is problematic because the method itself is grounded in a deficient grasp of German historicism that systematically excludes both aesthetic considerations and divine action from historical investigation. Adopting this approach, scholars have (perhaps inadvertently) closed themselves off from recognizing God’s activity in history.

Uniting History and Theology closely examines three prominent thinkers who have attempted to bridge history and theology: Martin Kähler, Wolfhart Pannenberg, and N. T. Wright. Heringer argues that all three have failed in their efforts to unify history and theology because they have not rejected the historical method as the primary framework for understanding past events. Instead, they have attempted various “mixtures” that continue to prioritize historical methodology over theological considerations.

Heringer’s critique goes beyond individual scholars to address the basic assumptions of the historical method itself, arguing that this methodology operates with presuppositions that are inherently incompatible with Christian faith. Its commitment to naturalistic explanation effectively eliminates the possibility of recognizing divine intervention or “supernatural” causation in historical events.

Rather than proposing a new “universal” or “public” historiographical method, Heringer advocates for what he calls “boldly Christian history.” This approach would allow Christians to investigate the past with distinctly Christian convictions and faith commitments. Important for his proposal, Heringer urges that there is no such thing as a “pure” historical method: All historical investigation is shaped by underlying theological and philosophical assumptions.

Heringer’s work thus contributes to growing criticism of historical-critical methodology among theologians and biblical scholars, offering a radical alternative that prioritizes theological conviction in historical investigation.

Heringer’s work is the focus of a sophisticated analysis by Chris Tilling, “Down with This Sort of Thing: Seth Heringer and the End of the Historical-Critical Method,” Journal of Theological Interpretation 16, no. 2 (2022): 275–92. https://doi.org/10.5325/jtheointe.16.2.0275. And Heringer responds to Tilling here.

Want to Read More?

Craig Bartholomew, C. Stephen Evans, Mary Healy, and Murray Ray, eds., “Behind the Text”: History and Biblical Interpretation, Scripture and Hermeneutics 4 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2003). ISBN: 9780310234142. 576 pp.

Stephen B. Chapman, “Historical Criticism, Moral Judgment, and the Future of the Past,” in A Sage in New Haven: Essays on the Prophets, the Writings, and the Ancient World in Honor of Robert R. Wilson, ed. Alison Acker Gruseke and Carolyn J. Sharp, Ägypten und Altes Testament 117 (Münster: Zaphon, 2023), 297–307.

Raymond C. Van Leeuwen, “The Quest for the Historical Leviathan: Truth and Method in Biblical Studies,” Journal of Theological Interpretation 5, no. 2 (2011): 145–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/26421421. Available here.