Theological Interpretation of Scripture Matters—14

The Role of the Reader

Our Current Situation

Well into the Reformation period, the role of the reader in biblical interpretation remained largely unexamined. Problematic readings were held at bay, or dismissed altogether, often through recourse to the Rule of Faith; or they were minimized simply by the theological and hermeneutical formation of interpreters within organic and established ecclesial frameworks and institutions.

Enlightenment-inspired hermeneutics downplayed (and continues to downplay) readerly engagement, given its ultra-commitments to neutral, dispassionate, scientific exegesis and to its concomitant depiction of the interpretive process as the excavation of texts in search of the author’s original intent.

Accordingly, the twentieth century introduced what can rightly be described as tectonic shifts in our understanding of the role of readers in biblical interpretation. It is not that readers suddenly became more active, but that their activity all along began to be realized. Additionally, we might say that readerly subjectivity experienced an uptick as the Bible became increasingly untethered from its ecclesial mores.

More generally, philosophical developments (think of Martin Heidegger [1889–1976] and his influence on Rudolf Bultmann [1884–1976], and especially of Hans-Georg Gadamer [1900–2002]) contested the possibility of presuppositionless interpretation. Gadamer urged that readers cannot avoid bringing their horizons of understanding to their encounters with the text. His understanding of a “fusion of horizons” between text and reader has become axiomatic in much biblical interpretation since the 1970s. Paul Ricoeur (1913–2005) claimed that meaning occurs at the intersection of textual interests and readerly interests.

More recently, theorists such as Wolfgang Iser (1926–2007) and Umberto Eco (1932–2016) have demonstrated how texts invite readerly participation. In different ways, literary and cognitive theorists (e.g., cognitive narratology) opened space for readerly involvement, including theological engagement. And interest in discourse opened further space for exploring how texts and readers (or auditors) continue to interact in ever-new contexts.

These developments press the point that meaning cannot be reduced to a singular, past moment, such as the ancient generation of a biblical text or its first reception. At the same time, they show that readerly participation is not (or need not be) an invitation to a hermeneutical Wild Wild West, since interpretive work is constrained, first, by the texts themselves (e.g., philology, literary structure, genre), and, second, by the cultural encyclopedia informing a text.

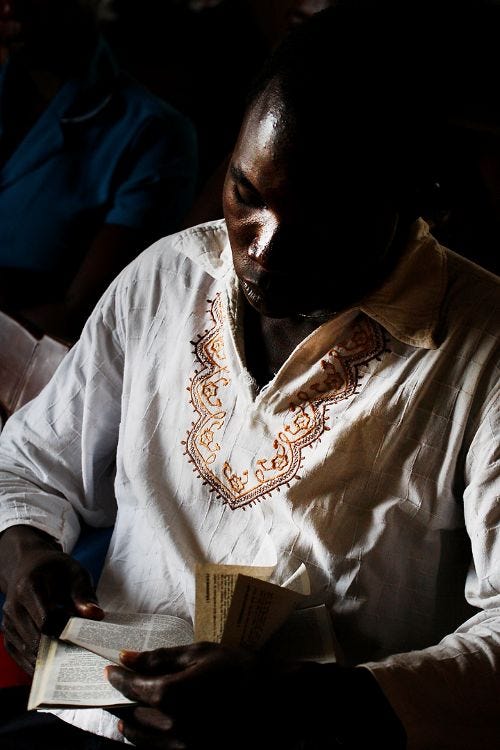

Moreover, the potential—even the probability—of diversity among readings from different reading communities constitutes a twofold invitation: to humility (given the inherent partiality of any one reading) and to biblical interpretation as a communal (including global and historical) enterprise (where this diversity is received, explored, and examined).

Readers and Theological Interpretation

What does all of this have to do with the theological interpretation of Scripture? To borrow a phrase from Paul: Plenty! And in every way!

Clearly, theological interpretation of Scripture is not a new practice, but an ancient one. It has deep roots in the early church and the New Testament era—and, indeed, in Jewish reception of Israel’s Scriptures during the Second Temple Period. For them, though, the work of interpretation was deeply embedded within communities of faith, theological through and through.

What is new about the contemporary enterprise of theological interpretation is a consequence of the loss of earlier taken-for-granted formative practices and institutions. Simply put, “serious study” of the Bible in the modern era takes place largely apart from congregations and, instead, mostly follows guild-accredited protocols increasingly unrelated to the religious significance of those texts. In other words, theological interpretation—at least in the West and in those areas of the world that have imported and ingested Western modes of interpretation—must be recovered. To put it differently, theological readers are typically not formed in our institutions of higher learning, seminaries included, so they must be reformed—or, at least, formed in alternative ways.

What sort of formation do theological interpreters need? If, as theological interpreters, we realize that reading Scripture is a conversionary enterprise, what conversionary habits help to form its readers? Here’s the beginning of a list:

A vital ecclesial home

Missional engagement

Lively engagement with the Holy Spirit (a sine qua non for early-church interpreters!)

The cultivation of such interpretive virtues as self-reflexiveness, humility, hospitality to people not like me and to readings not like mine, discernment, and phronesis (practical wisdom)

Ongoing (forms of) catechesis

Recommended Reading

[Note: As an Amazon Associate, I may earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase. This doesn’t affect the price you pay and helps support this website.]

Stephen E. Fowl and L. Gregory Jones, Reading in Communion: Ethics in Christian Life (reprint ed., Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1998). ISBN 9781579101244. 176 pp.

In this game-changing book, Fowl and Jones argue that the primary vocation of Christ-followers is to embody Scripture within their worlds. Accordingly, they emphasize developing moral and theological judgment, and theological virtues like reconciliation and forgiveness, in the context of vital relationships within a Christ-following community. Challenging American individualism and autonomy, the authors advocate reading Scripture communally and listening to outsider voices.

Richard S. Briggs, The Virtuous Reader: Old Testament Narrative and Interpretive Virtue, Studies in Theological Interpretation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2010). ISBN 9780801038433. 272 pp.

Briggs explores the moral character and virtues needed to read the Old Testament well, arguing that Scripture itself projects ideal virtues for readers. He examines how biblical texts cultivate such interpretive virtues as humility, wisdom, trust, love, and receptivity. Briggs draws virtues from the narratives themselves, demonstrating connections between the reader’s character and the act of interpretation. He challenges detached objectivity, advocating instead for virtuous engagement.

Greg McKinzie, The Hermeneutics of Participation: Missional Interpretation of Scripture and Readerly Formation, Studies in Missional Hermeneutics, Theology, and Praxis (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2025). ISBN 9798385213061. 272 pp.

McKinzie develops a missional hermeneutic centered on participation in God’s mission. He argues that the church’s participation in God’s mission is constitutive of Christian theology, and this leads to his proposal of a hermeneutic in which participation in God’s mission is a precondition for faithful interpretation. McKinzie emphasizes readerly formation through the church’s embodied practices and the interpretive function of the Rule of Faith. Mission becomes the ecclesial location from which theological reading emerges, making participation essential to understanding Scripture. [See my earlier comments, here.]

Daniel Castelo and Robert W. Wall, The Marks of Scripture: Rethinking the Nature of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2019). ISBN 9780801049552. 192 pp.

Castelo and Wall propose an ecclesial analogy for understanding Scripture, applying the four Nicene marks of the church—one, holy, catholic, and apostolic—as marks of Scripture itself. This stimulating proposal opens with a chapter on “The Ontology and Teleology of Scripture” and ends with a final chapter focused on “The Church’s Practice of Scripture”; these two chapters relate directly to our concern here with readerly formation for engagement with Scripture.

Thanks, Joel. This just came up in our Tavern Theology discussion last night on the reader’s role and reading Scripture for formation. I’ll share this with the group’s page.

McGilcrist has rejected the old left brain right brain in favor of 30 years of research and 5000 references producing a completely new way of understanding how the brain works.